Data-informed design experiments

Assessing the effectiveness and appropriateness of design for behaviour change

- timespan2019 → 2020

- capabilitydesign research

design for behaviour change

When intentionally changing behaviour through design it is important to understand the degree to which that change manifests itself and what the consequences that the introduction of the design has. However, changing behaviour is something that takes a long time to materialise durably and thus conventional qualitative user-centered approaches to evaluation may not be the most suitable. On the other hand, quantitative approaches measuring only the outcomes of the behaviour similarly do not provide detailed insight into the performance of the intervention. Hence for my graduation project I explored how designers can be supported in the critical assessment of the effectiveness and appropriateness of designs for behaviour change through combining several quantitative and qualitative data sources.

The effect of a design intervention in changing behaviour is generally measured in terms of its effectiveness, the long-term consolidation of the intended effect. Design interventions can produce effects like a reduction of water use and electricity consumption, however, in follow-up studies those positive effects are often not sustained (Abrahamse et al., 2005). Thus there may be another factor at play that influences the effectiveness over time. This is the appropriateness of a design, the quality of being proper and suitable to the user’s context.

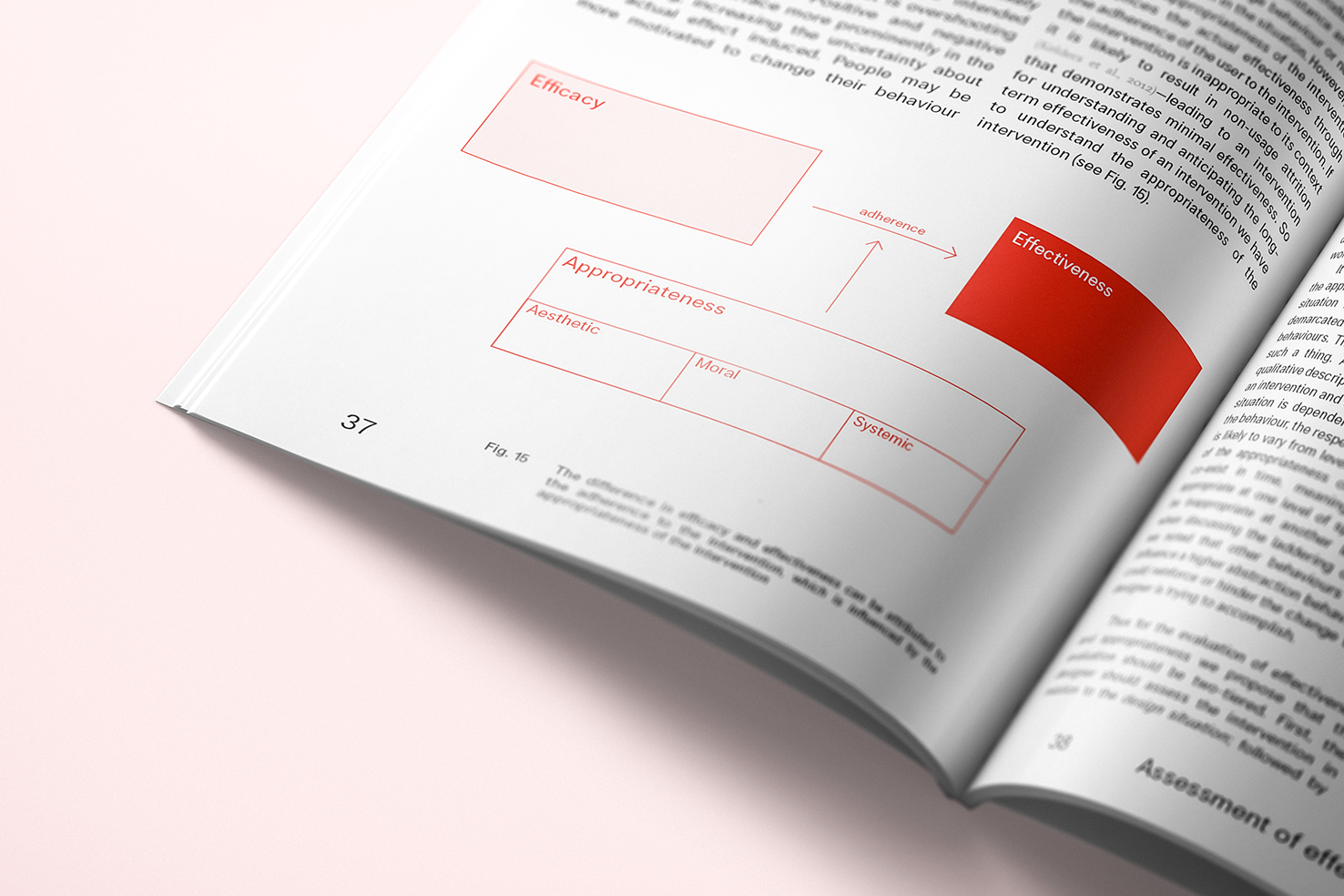

Theory development

I operationalised these two concepts into a theoretical model that describes the transition of a design being efficacious to effective. Right after introduction of the design positive and negative effects may surface more prominently, increasing the uncertainty about the actual effect induced. For instance people may be more motivated to change their behaviour, or do not yet see all the capabilities that the design has to offer. As these effects fade over time, the actual design qualities of the intervention play a role in the formation of a stable bond between the user and the thing when integrating it into their daily lives. This is where the appropriateness comes into play, as all the elements that spark irritation or frustration influence the level to which they adhere to use, directly impacting the effectiveness.

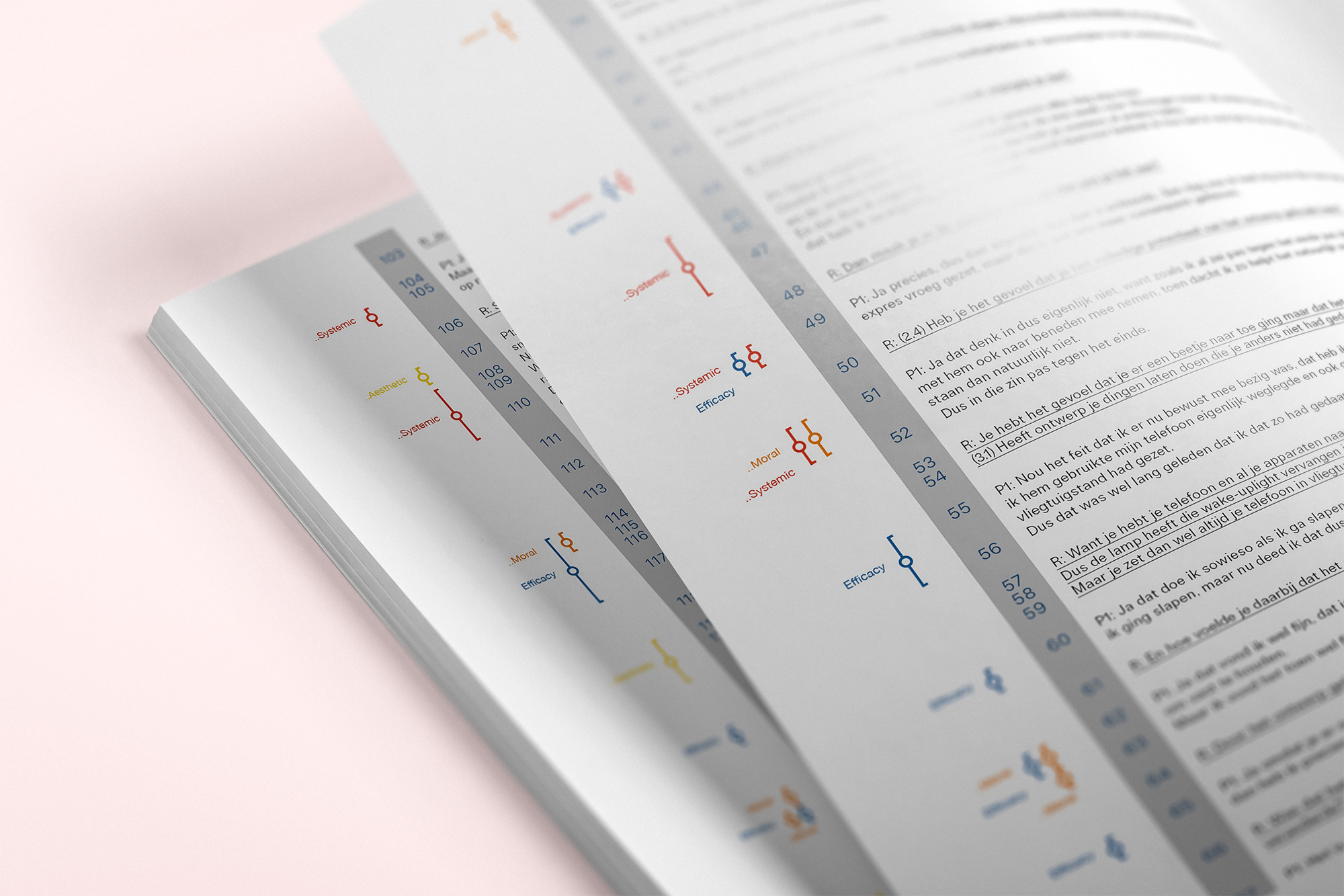

This appropriateness can be differentiated in three types: aesthetic, moral and systemic appropriateness. Aesthetic appropriateness concerns the aesthetic appreciation of the intervention in relation to its effect; building on the aesthetic principles of achieving the maximum effect with the minimum means and being most advanced yet acceptable (Hekkert, 2006). Moral appropriateness entails the tolerance of the user towards the exerted influence by the intervention (Tromp et al., 2013). Systemic appropriateness relates to the fit between the intervention and the greater whole and the ability for people to integrate and appropriate the design into their daily lives and practices—as well as the (unexpected) consequences caused by the introduction of the intervention.

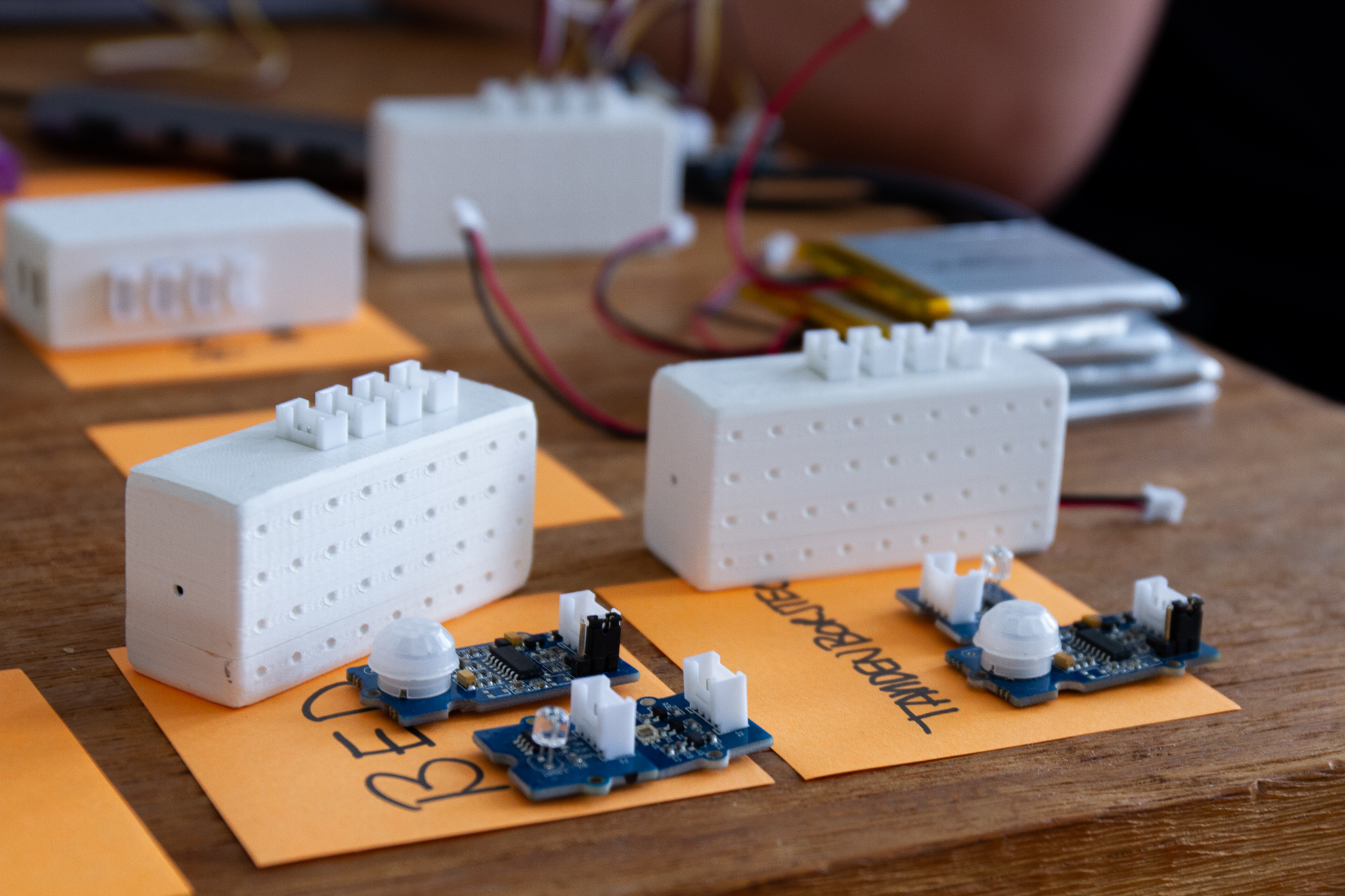

Design experiments

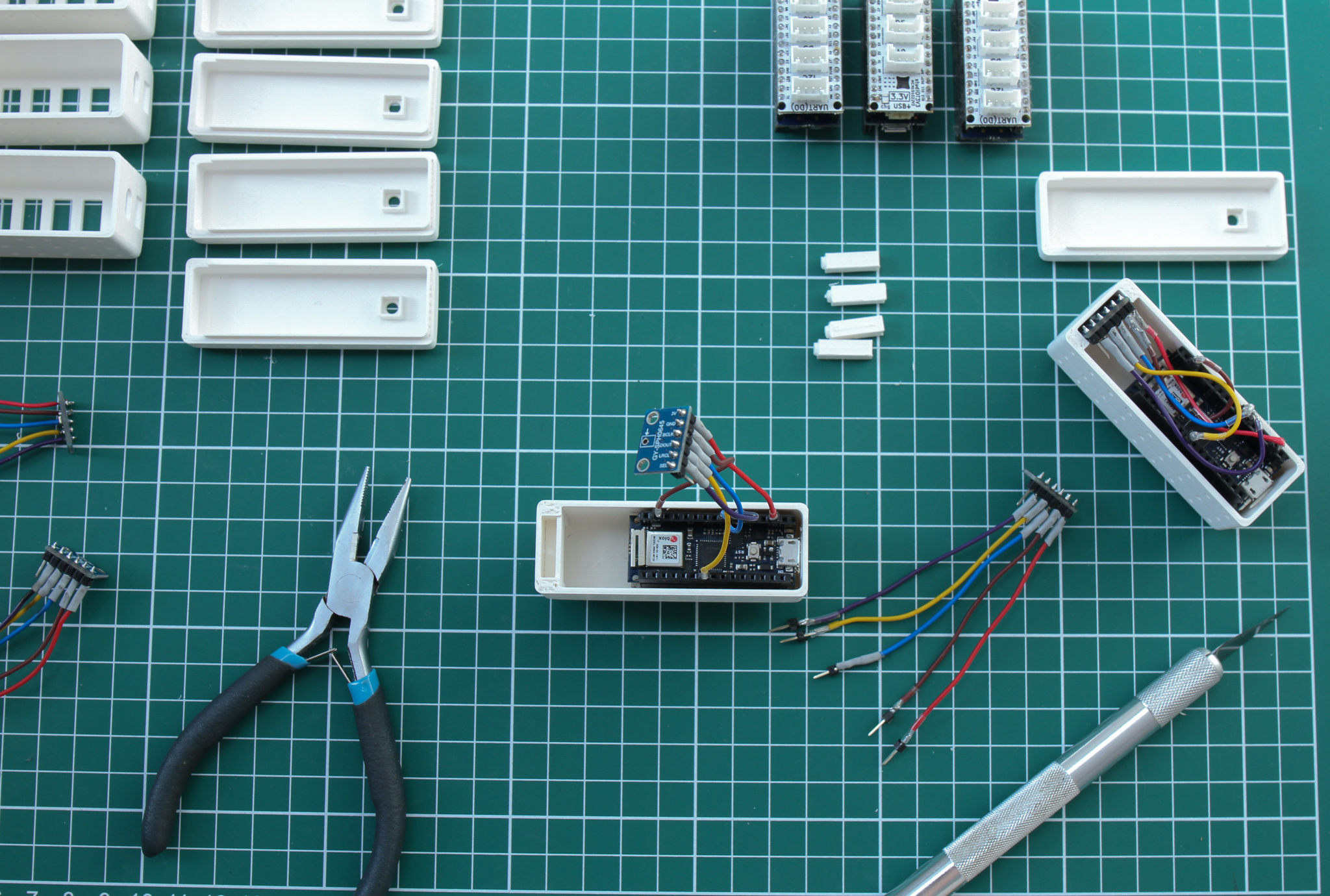

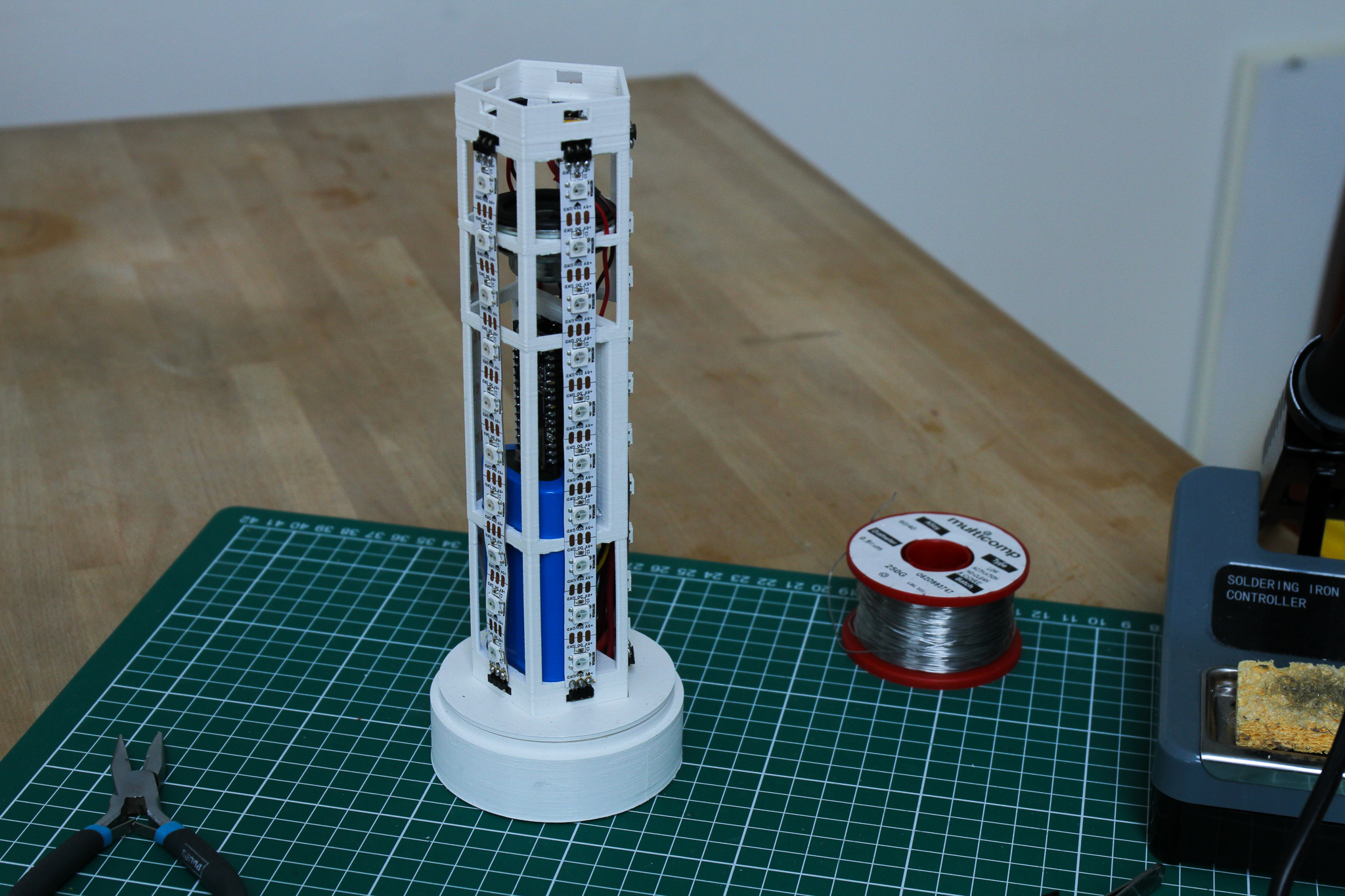

The relations in the theoretical model were experimentally explored by performing two design experiments in the context of an end user. As I was interested to explore rich everyday environments as the context of the research, the focus of the experimental part of the research was on sleep behaviour. The appropriateness was varied in a controlled way by selecting two different manifestations of design while keeping the working principle the same; as through the specific design and formgiving choices that designers make they directly influence the appropriateness of a design. Hence I designed, based on existing concepts, an interactive bed light and a chatbot that both aimed to harmonise people’s sleep and wake times.

Sources of data

In contemporary design practice designs are often evaluated through user tests where (prototypes of) a product or service are used to elicit user response—as they are the ‘expert of their own experience’. However, when it concerns behaviour it is arguable whether that is the case as well. Behaviour can be something that people are ashamed of to discuss honestly resulting in socially-desirable answers; or is something that simply falls outside their sense of perception and relevance. On the other hand, relying mainly on quantitative, or data-driven, approaches is insufficient as well. Approaches like A/B testing and usage analytics provide with insight into the performance of the product design, however, they rarely expose the reasons and values underlying the observed behaviour. Besides, it is arguable whether interaction with a product only can provide with enough insight to understand rich behavioural patterns that may not always be influenced by the intervention.

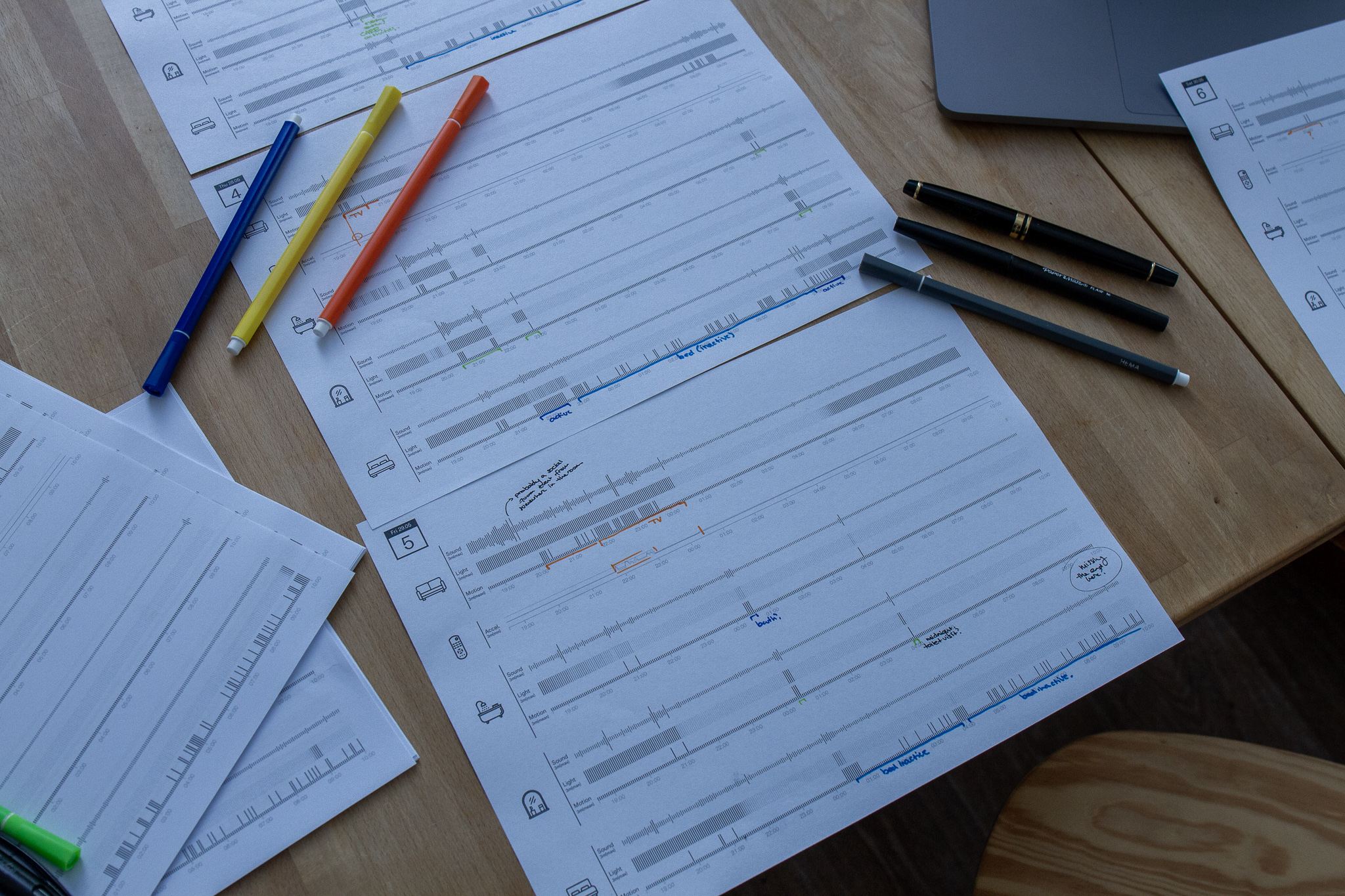

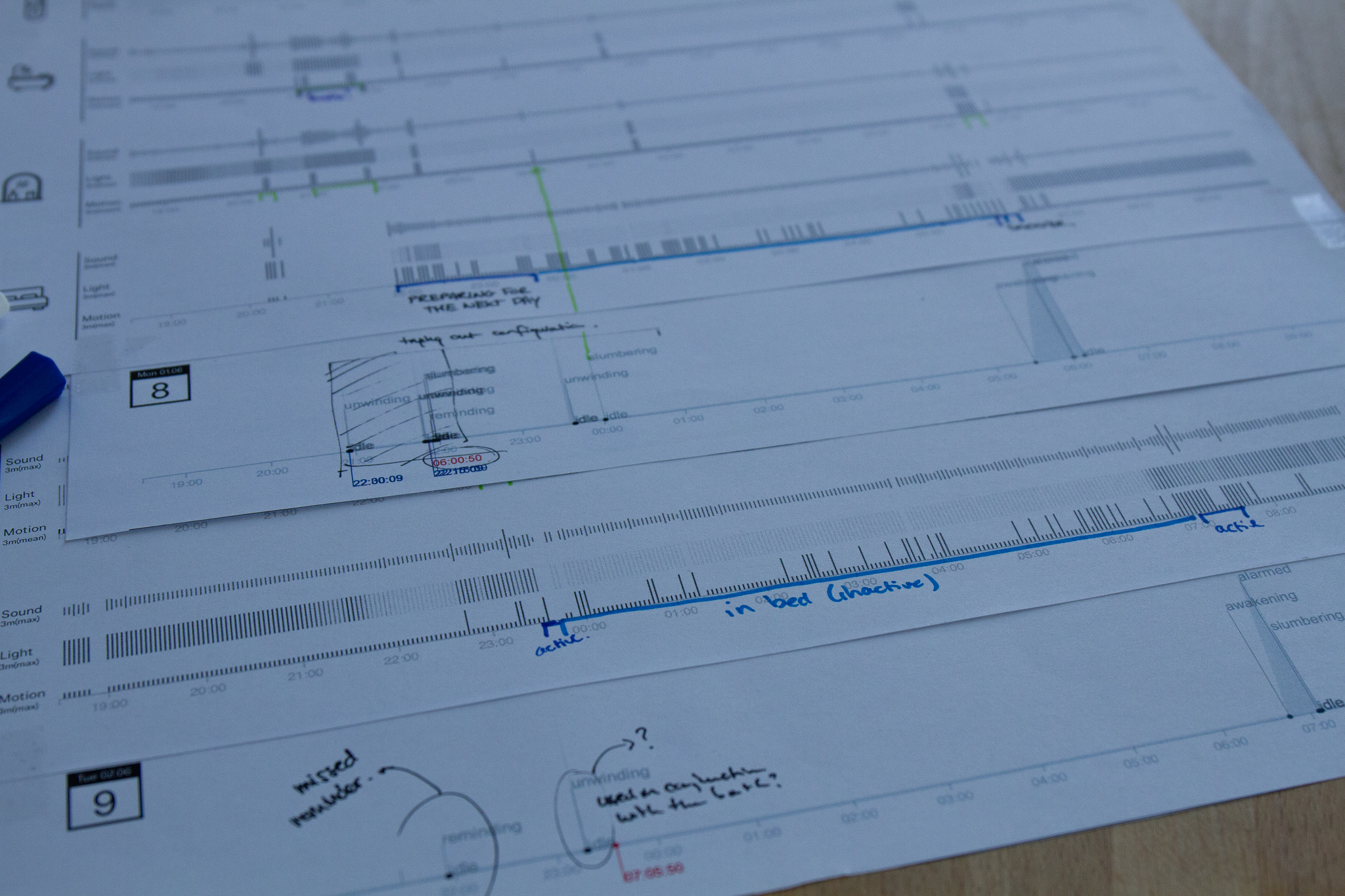

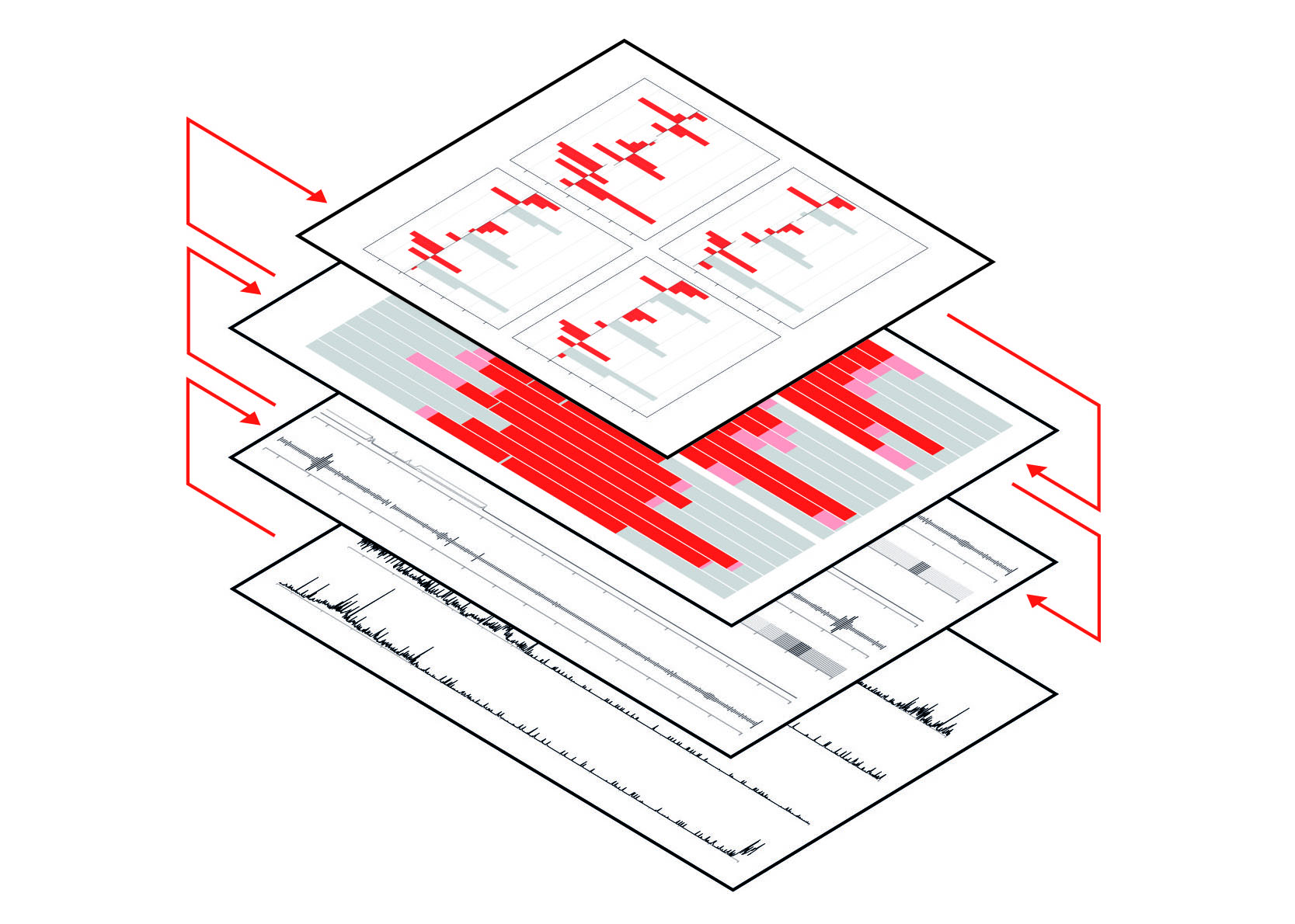

As each approach and respective sources of data has their inherent limitations and blindspots, I gathered data from various sources: sensor data from an ecology of instrumented things, user-product interaction data and ethnographic data from interviews with the participant before and after use.

These different sources of data have a variety of characteristics that go beyond the traditional division between quantitative and qualitative—as they span factors like longitudinal and momentary impressions of the situation, interpretations of the situation from people and things, and objective observations and subjective inquiries in values.

Data analysis

The main aim for the data analysis was, using the various sources of data, to gain insight into the efficacy and appropriateness of the design intervention in order to anticipate the effectiveness. For this it was imperative to turn the data into material that could be used by designers to compare and contrast the various sources of data.

Contributions

The outcomes suggest that the theoretical model can be used to anticipate the effectiveness and identify elements that need to be addressed to improve that effectiveness. Additionally, the model can also be applied in a preventative way, identifying elements of inappropriateness early on in the design process.

The data generated by things and designs in the home context allowed to do longitudinal remote research which, apart from being a proper research approach in a pandemic situation, allowed to see the actual performance of the design instead of measuring mere outcomes of the behaviour. It was possible to observe whether the mechanism of the design was induced and thus provides evidence as to whether the design leads to the desired change behaviour.

By turning the sensor data in a design material through the use of the data worksheets, designer are better equipped for using such types of data without having to understand the technology behind it. This creates a more transparent process where interpretations can be traced back to the ‘raw’ data, as well as facilitate cooperation between data scientists and designers.

The results of the project were compiled into a comprehensive thesis, which can be found in the TU Delft repository.